REVIEW: A Natural History of Dragons by Marie Brennan

|

Title: | A Natural History of Dragons: A Memoir by Lady Trent |

|---|---|---|

| Author: | Marie Brennan | |

| Pub Date: | February 5th, 2012 | |

| Chris’ Rating (5 possible): |     |

|

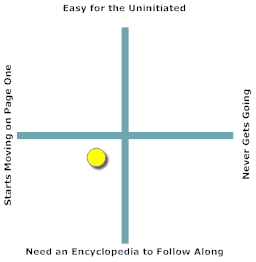

| An Attempt at Categorization | If You Like… / You Might Like… | |

|

||

One of the most interesting themes I’ve found in science fiction is the genre’s complex relationship to science itself: most science fiction stories are simultaneously promoters of science and cautionary tales, warning us of discovery’s ethical dangerous. This makes for an interesting and powerful theme to explore, what with humanity’s unbridled capacity for discovery. But for all of its power, it is a theme which fantasy addresses all too rarely, which is why it was such a delight to recently read Marie Brennan’s A Natural History of Dragons: A Memoir by Lady Trent.

I grew up on scientist adventurers: Verne’s Professor Arronax (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea), Doyle’s Professor Challenger (The Lost World

), and Wells’ The Time Traveler (The Time Machine

) all thrilled with the promise and possibilities reason could bring. These characters practiced and preached a set of positivist values, an Enlightenment tradition untrammeled by the softer complexities of Romanticism. And when a few years later I discovered the history of science, in particular through works like C.W. Ceram’s Gods, Graves and Scholars

, Jane Goodall’s In the Shadow of Man

, and Farley Mowat’s Woman in the Mists

I could see how real scientists worked and struggled to fit such values into a more complex world than the fictional.

For all of the positivist values promoted through the works of early science fiction, most of those books derive their conflict from the tension between their characters’ full-throated devotion to positivist principles and the subtler risks – ethical, philosophical, and existential – which science exposes us to. Verne’s Nemo – and his mad political philosophy – is an ethical exploration of the militaristic consequences of science, of technology’s capacity for both good and evil. The dismissal of Challenger and Summerlee’s findings in The Lost World explores how society treats discoveries which fly in the face of accepted wisdom, a social statement on public attitudes to science if ever there was one. And Wells’ The Time Machine

is nothing if not a commentary on man’s self-destructive tendencies, offset by the Time Traveler’s genius invention of the time machine itself and his yearning to explore.

Such an exploration of reason, such an application of rational thought, is often inimical to much fantasy. So much of the genre relies on the irrational that it is easy to get uncomfortable when put beneath the magnifying glass. Fantasy generally explores different themes, leaving an exploration of science to science fiction. Some fantasists – notably Patricia C. Wrede in her Frontier Magic trilogy, Michael A. Stackpole in his Crown Colonies trilogy

, and much in the steampunk vein – have incorporated such scientific themes, but their approaches tend to use science as a device for getting characters into trouble. Science is not the heart of the story: war or some other life-or-death struggle divorced from science provides the conflict. While such stories may be exciting, I usually find myself disappointed that the science gets short shrift.

But Marie Brennan’s A Natural History of Dragons keeps the science front-and-center, and builds tension and conflict naturally from that core. The way in which she achieves this effect is particularly interesting because it is simultaneously more obvious and more subtle than I would have expected. The obviousness stems from the book’s historical models: while it is a secondary fantasy, it is structured along the lines of the memoirs and stories of late Victorian (British) natural philosophers.

I am amazed that I don’t see this approach more frequently in fantasy. For 18th and 19th century readers in the Western world, journeys into Africa or South America would have been the equivalent of a secondary-world fantasy. Their settings and the cultures encountered would have been so alien as to be unrecognizable. They would have to establish and contextualize the strange environment, to explain its characteristics in both sensual and intellectual modes. In other words, the historical models for A Natural History of Dragons would have relied on the same type of world-building as any fantasy.

The basic structure of the story traces a recognizable path: the narrator’s development of scientific fascination, her initial discoveries, youthful exuberance, and systematic maturation as those discoveries mount is a natural progression recognizable, I think, to any adult. Because the novel is set during a time when people are ignorant of dragons, the ignorance of broader society (and initially of the narrator) is shared with the reader. We learn about Brennan’s secondary-world along with our heroine as she and her colleagues make what might seem to be basic discoveries. This evokes the same sense of obviousness we get when we look back at the scientific discoveries of yesterday.

The more subtle key to the novel’s success is maturation. A Natural History of Dragons is presented as a memoir written by the now-elderly Lady Trent, a rather feisty and by implication controversial natural historian. In the hands of a weaker author, her anachronistic attitudes (for her time, which is plainly modeled on the 19th century as conveyed by both voice and details in the text) would have always been present. From childhood, she would have been confident of her abilities despite prejudices against her gender, she would have always been respectful of other cultures, would have naturally become the intellectual and moral center of any expedition she took part in despite the many cultural factors stacked against her, etc. She would have been a modern heroine inserted into a historical world, and would naturally have triumphed over historical backwardness. The world would revolve around her because she is Our Heroine, and so a special snowflake.

Brennan neatly avoids this trap, and by doing so makes the book a delight to read. Yes, our heroine is special. But this is a tale of her youth, before she became Lady Trent with the notoriety such a title suggests. The narrator shows herself to be merely one step out of alignment with the mores of her time both during her youth and presumably at the time when the memoir is written. By alluding to her earlier works, and repudiating the prejudices she espoused therein, the narrator simultaneously acknowledges the problematic tendencies of the source time period, and provides justification for the narrator’s anachronism. The narrator does not share the attitudes of the time period of which she is writing because she – and presumably much of her society – has matured in the intervening years. We can plainly see the distinction between the narrator and her younger self, and this serves to further ground us in the character and the world. Yet the whole structure is made even more plausible by showing us the seeds of the opinionated older narrator in the actions and words of her younger self. It is a very neat trick.

Brennan’s character is clearly of scientific mind, and the focus in much of the book is on the science itself. Initially, one can be forgiven for thinking it a tale of simple positivist boosterism: after all, so much of its historical roots were exactly that. But as the adventure ramps up, Brennan introduces suggestions of a flip side to scientific development and discovery. This squarely puts the novel in the conflicted tradition of Verne, Doyle, or Wells. Yet unlike these far earlier writers, Brennan neatly balances the science with an inner emotional journey that at times can be quite touching.

If I have one complaint about the book, it is that it is too short. Partly, this perception is a selfish one: I would have gladly spent more time in this world, with these characters, and with the voice in which the novel is written simply because of how much fun I had with it. But structurally, while the book works as a standalone novel, it did leave me wanting more.

I don’t know (read: my Google Fu was unable to determine) if A Natural History of Dragons This is plainly a memoir of Lady Trent’s youth, and she explicitly references other (it seems wilder) adventures which follow. At the same time, the implicit risks of scientific discovery are brought to the fore near the story’s conclusion. They are not resolved or developed in any meaningful sense, but rather are addressed at best temporarily, which while satisfying in this one volume does beg for further development. Both of these facts suggest that more books may follow, and I for one would be very happy if they do. is the start of a series or a stand-alone one-off.

(UPDATE: Today’s Shelf Awareness for Readers has a nice write-up of the book, where they mention that it is the first installment in a planned series.)

I would also be remiss if I did not mention that the novel is a work of art in hardcover. I would recommend it on the strength of its design alone (with great deckled edges and a sepia-toned font which further evokes that Victorian sensibility), but for me, Todd Lockwood’s excellent illustrations seal the deal.

I strongly recommend A Natural History of Dragons: A Memoir by Lady Trent to anyone who has a taste for Victorian-inspired fiction, who loves the long age of discovery that spans from the Enlightenment through to the first World War, or who enjoys classic science fiction like Jules Verne, Arthur Conan Doyle, or H.G. Wells.