REVIEW: Planesrunner by Ian McDonald

|

Title: | Planesrunner |

|---|---|---|

| Author: | Ian McDonald | |

| Pub Date: | December 6th, 2011 | |

| Chris’ Rating (5 possible): |     |

|

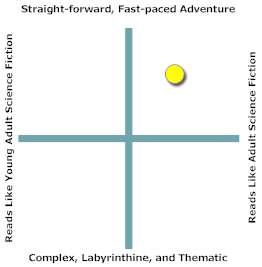

| An Attempt at Categorization | If You Like… / You Might Like… | |

|

||

As I’ve mentioned before, I am a huge fan of Ian McDonald’s adult science fiction. His complex, multi-layered plots and penchant for near-future science fiction set in non-western cultures (Africa, India, Brazil, Turkey, etc.) have always struck me as interesting, engaging, ambitious, and structurally complex. So when I heard that Pyr was going to be releasing a new YA novel by Ian McDonald entitled Planesrunner, I jumped at the chance to read it.

McDonald has earned a large, loyal, and very much deserved following for his adult fiction, I don’t know if the decision to market this particular story as YA lay with the author, his agent, or with his publishers, but it does make reviewing the book an interesting challenge. UPDATE: but his foray into MG/YA fiction represents an interesting critical challenge. The YA and SF genres have different (though overlapping) conventions which stem from both their respective histories and their divergent audiences, and it is unclear through which lens we should look at Planesrunner. What comes first: the science fiction, or the YA?

Planesrunner is told from the perspective of Everett Singh, the fourteen year old son of a quantum physicist involved in the development of doorways onto parallel worlds. Everett watches his father get kidnapped, and then finds that he alone has the clues and capabilities to rescue him.

Judged solely by the protagonist’s age, Planesrunner falls firmly into YA territory. Though the book opens in London, McDonald’s hero comes from a Punjabi background, and McDonald’s excellent ear for local cultures comes through in Everett’s voice. Particularly in the novel’s first third, McDonald paints Everett in solidly contemporary British colors, albeit filtered through his Punjabi background. Everett’s cultural background can likely best be compared to that of Jessminder “Jess” Bhamra in the excellent Bend It Like Beckham

: to say that Everett is a soccer-loving British boy tells only half the story, while to say he is Punjabi does the same. This is a blend culture more accessible to western readers than the India McDonald took us to in his (adult) Cyderabad Days

, but it is definitely not the whitebread England of Harry Potter. As always, I applaud McDonald’s presentation of cultural complexity.

The first third of the novel focuses on Everett’s reactions to his father’s kidnapping. From the high-powered opening, the story’s pace slows down significantly as we learn more about Everett’s family background (his parents have split up, he has a younger sister, etc.) and we get gradually introduced to our protagonist. We learn about Everett through his interactions with his mother, his soccer team buddy, the police, and his father’s co-workers. Throughout this process, we gradually learn more about the work his father does, and about the parallel worlds that he helped discover. This part of the book is written with McDonald’s typical skill, providing a good feel for Everett, his values, his cultural background, and his life. We grow to care about him, and get engaged in his desire to save his father. All of this is good, however by the standards of contemporary YA it happens rather slowly. Most contemporary YA that dives into the action the way this story does maintains and rapidly escalates the tension from page one. Here, the tension is maintained but its escalation unfolds more slowly. It is effective, but it has more of the feel of an adult novel than a typical YA story.

Once Everett deduces that his father has been taken to the parallel world of E3 and follows him through the gates, the book’s pace accelerates substantially. First, the alternate reality Everett crosses into is a vastly different London, where oil was never discovered. As a result, its 21st-century society runs on coal-powered electricity and has no access to technology we take for granted (e.g. plastics). It is a delightful and compelling steampunk world, complete with vast airship fleets. The concept of a 21st-century London where oil had never been discovered is an interesting one, and McDonald does an excellent job of rendering its technological development believably. But while he does a fine job of nailing the technological/scientific world-building, I am less sold on the cultural flavor of his alternate London, which blends contemporary and pseudo-Victorian sensibilities.

On the one hand, we see that the alternate world has values and a cultural background commensurate or at least compatible with those of our modern world. The villains in E3 are quite at home in skyscrapers, modern dress, and with modern weaponry. But they are set in opposition to a romantic rabble of airship sailors who dress, talk, and generally act like they stepped out of the Victorian era. Perhaps this disconnect is part of McDonald’s point, but upon reflection, I found myself doubtful. Nevertheless, it is a testament to McDonald’s skill at world-building that these quibbles only arose upon reflection: while reading the story, I found the world compelling, engaging, and believable.

Once in this new world, Everett quickly joins up with that staple of the steampunk sub-genre, a crew of airship pirates sailors. They are second-class citizens presented as a rough-around-the-edges but still lovable rabble, quasi-Romany in nature. The characters Everett runs into, in particular his fiesty love-interest Sen, her adoptive mother (the captain), and her Bible/Shakespeare-quoting crewman are all extremely distinct, very interesting, and very engaging. In portraying both this world and the harsh underbelly of its society, McDonald made an interesting authorial choice: most of these characters speak in polari, which IRL is a cant slang developed in the British theater community in the 17th and 18th centuries. McDonald portrays this dialect directly in dialog, making it hard to parse for the uninitiated. I found myself torn as to its effectiveness.

The strategic use of polari deepens the credibility of McDonald’s alternate world. Yet at the same time, it decreases the accessibility of that world. As an American whose only previous encounters with polari had been limited to a handful of phrases in a few episodes of Porridge while living in Europe, I found that it took real work to decode what characters in Planesrunner

were saying. Interestingly, Everett had very little trouble doing so: it is possible that growing up in London, he would have had more exposure to polari than I have had growing up in the States. Readers as unfamiliar with it as I was might find that it takes a bit of effort to get through. Overall, this strategy marks an interesting choice, and one that in general McDonald pulls off effectively. However, it is a choice that I have rarely seen in YA. Experienced genre readers will probably just accept it and make use of the glossary at the end of the book, but I am less certain that YA readers will be willing to invest the same amount of effort.

The biggest weakness I found in Planesrunner was that once Everett stepped into the parallel world, it seemed as if he had entirely forgotten about the mother and younger sister he left behind. To some extent, this is a natural consequence of the plot’s focus on rescuing his father. Nevertheless, I had the impression that themes of Everett’s family introduced at the book’s opening remained unaddressed (let alone resolved) at the book’s end. Above all, it is this fact that makes the book feel more like an adult SF novel than a YA SF novel.

Themes of family, of choosing/balancing sides, and of cultural identity are all frequently explored in YA. One can argue (and I’ve done so on this blog before) that at some level all YA novels address the challenge of finding one’s place in a complex, multi-layered, and ambiguous world. McDonald sets these themes up fairly well in the opening of Planesrunner, but fails to follow through on them by its end. Themes of family get re-introduced, with the focus on Everett’s place within the airship’s “adopted family”, but it never ties back to the family he left at home. Perhaps as the series continues we will return to these themes and gain some closure. But stretching a single unresolved thematic arc across a series and without clear inflection points in each installment is something adult series may pull off, but flies in the face of typical YA conventions. It is one thing to end the plot of the first book on a cliffhanger as McDonald (more-or-less) does, but to leave thematic threads dangling (as opposed to tied, whether loosely or strongly) weakens the book’s emotional resonance.

Overall, Planesrunner is a solid adventure. Read as such, it is perfectly enjoyable. Fans of adult science fiction will find it especially satisfying, and will likely find it fast by the standards of the adult genre. Fans of YA science fiction will likely enjoy it as well, though I suspect that long-term it won’t be as memorable as more tightly themed YA novels. Readers of McDonald’s earlier work will enjoy Planesrunner

for how it builds on McDonald’s strengths and how it diverges and expands on his previous patterns. However, readers looking for the thematic, structural, and sociological complexity of McDonald’s adult novels won’t find it here. That complexity may exist below the story’s surface, incorporated into the story’s world-building, but Planesrunner

is a simpler, more adventure-focused story than McDonald’s earlier work. In general, I found Planesrunner

a fun if only partially-satisfying read, but I am definitely invested enough to pick up the next book in the series when it comes out.

Hi Chris! A quick note regarding this “I don’t know if the decision to market this particular story as YA lay with the author, his agent, or with his publishers…” Ian McDonald’s intention from the get-go was to write a book that would get young boys to read. There was no marketing angle to this being a book for ages 12 & up, it was written with that reader in mind. You might want to check out this recent interview in which Ian explains why: http://www.sfsignal.com/archives/2011/12/exclusive-interview-ian-mcdonald-talks-about-his-new-novel-planesrunner/#comments

Hi Jill! Thanks for the pointer to the great interview. Definitely great to see more of Ian McDonald’s intentions/thinking behind the book.