The Grisly Anatomy of Horror: Methods in Horror Fiction

Halloween is upon us, and I can’t think of a better season to consider the anatomy of the horror genre. I’m not looking for a definition of the genre (most definitions run along the lines of “the horror genre generates a feeling of terror or horror in the audience” – DUH!). Instead, the ghouls and ghosts and ninja pirates outside my door ravenously seeking my candy inspire me to ask the following questions:

- What kinds of emotional response can be evoked by the horror genre?

- How does the horror genre evoke that emotional response?

Terror, Horror, and Identification/Realization

Of course, all writing is manipulative to a greater or lesser degree. But horror especially plays on our ethos to achieve the author’s goal: eliciting a strong emotional response. This is the case whether we’re considering:

- classic horror novels

- Stoker’s Dracula

,

- Lewis’ The Monk

,

- most of Edgar Allen Poe

‘s work, etc.

- early 20th century weird fiction

- H.P. Lovecraft’s The Shadow Over Innsmouth

,

- Clark Ashton Smith’s The Dark Eidolon,

- Robert E. Howard’s Solomon Kane

stories, etc.,

- contemporary horror

- Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend

- Stephen King’s It

- Dan Simmons Drood

, etc.,

- certain strains of the New Weird

- China Miéville’s The Scar

,

- Jeffrey Ford’s The Physiognomy

, etc.

Horror makes use of three primary modes:

| Terror (Dread) | The fear of predicted or anticipated events. The fear of what is to come. |

|---|---|

| Horror (Revulsion) | The fear of events or facts that have already happened/been shown. Revulsion at what is perceived. |

| Identification (Realization) | Lingering terror or horror at the conclusion of a story that relies upon internalization of the story’s themes. |

Any particular work of horror can (and often does) utilize all three modes at different points in the story. I won’t bother commenting much on the first two (Terror vs. Horror) because a lot has already been said about that. If you’re looking for some of that discussion, a good starting point is the Wikipedia entry on Horror and Terror.

I would, however, like to spend a moment discussing the concept of identification. This is not horror in the “what’s that behind the door” (terror) or “my god that’s disgusting” (horror) variety. Instead, it is a thematic horror that lingers after the book has been closed. This type of horror relies on the reader’s self-identification with the story elements that had – until the climax – been the object of terror/horror. It is fundamentally the realization that “The monster is Us” and is often used in the most memorable horror stories. It is that sensation at the end of a horror story that leaves you feeling like:

- you could see yourself as the monster, and/or

- you would behave as the (doomed) protagonists were you in their shoes.

While the entire horror genre uses terror, horror, or both, I believe that the most-memorable horror also relies on this third mode for its resonance. Matheson’s I Am Legend would be unremarkable if not for its use of realization. Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death is powerful precisely because we identify with the doomed revelers.

So how does the horror genre evoke these three emotional modes? Just as with any genre, horror has its share of tropes. But I believe there are two tools which are universal across all of the sub-genres of horror (intrusion horror, zombie horror, vampire horror, etc.) and all of the mediums of horror (books, film, comics, etc.): uncertainty and horrific imagery.

Uncertainty: The Gasoline in the Horror Plot

Every story – regardless of genre – relies to some extent on uncertainty. We (the reader) are uncertain of what our hero is going to do next, or of how a situation will resolve itself, and so we keep turning pages. In the horror genre, our uncertainty is typically shared by the hero. The hero is uncertain of the monster: is it real? What is it? What are its weaknesses? What does it want? While on the journey with our hero, we share that uncertainty. Good horror is frequently written in either first-person narration or close-perspective third person. This is done specifically to put us in the hero’s head, to understand his perceptions of his situation. If the hero (and the reader by extension) were certain of the situation, then there would no fear, and thus no horror.

From a plotting standpoint, resolving this uncertainty gives the story its forward motion. It’s the gasoline that powers the story’s engine. Consider Stephen King’s Needful Things. In that novel, Sheriff Pangborn tries to unravel the mystery of why Castle Rock’s residents are suddenly killing each other. He is uncertain of Leland Gaunt’s intentions, and initially of his guilt. Similarly, Dan Simmons’ Drood is propelled by Dickens’ and the narrator’s desire to uncover the mystery of Edwin Drood. In James Cameron’s Alien

, the uncertainty rests around if and how Ripley and the rest of the crew will escape the xenomorphs. In the 1997 film Event Horizon

, the uncertainty stems from the Event Horizon‘s appearance and its strange gravity drive.

How the characters respond to these uncertainties elicits the sensation of dread (terror) or revulsion (horror). Just as your characters’ reaction to magic systems makes them believable in fantasy, so the characters’ reaction to uncertainty generates fear in the reader. This effect can be enhanced through the use of horrific imagery.

Imagery: The Keys to Horror

Effective horror imagery manipulates that part of our brain which our ancestors used to identify (and fight or flee) from threats. I believe that there are five principle types of horror imagery, each of which has different components and different effects:

| Imagery | Typical Effect, Method, & Examples |

|---|---|

| Mood |

|

| Manipulates our limbic system (that reptilian part of our brain that controls the fight or flight response). Dark, chilly rain forests replete with mysterious sounds still make us wary, despite the fact that most of us left the forest floor millenia ago. A fog-covered city street in the dead of night automatically puts us on our guard because our brain knows that “unnamed threats” can lurk in the mists. If your setting is built with imagery that can hide or hint at monsters, it can be used to make your audience receptive to the sensation of dread you’re seeking to instill. It can be a subtle effect, gradually building through layers of disconcerting and slightly shadowed images. Look to Poe or HP Lovecraft for great examples of how this can be done. | |

| Pin-point Terror |

|

| A more direct type of horrific imagery used to “jump start” the limbic system. If layering horrific imagery throughout your story produces the appropriate mood, throwing in explicit imagery of your monsters can be excellent punctuation. Be careful not to over-do it. You want to show enough of your monster to terrify your audience, but leave enough uncertainty for them to keep jumping at shadows. The classic image that comes to mind is eyes glowing in the dark. It makes us think of wolves in the night, monsters whose eyes you can see without any idea of how large or dangerous they are. This combination of immediate danger while maintaining uncertainty is a great way to up your audience’s heart rate. | |

| Repugnance |

|

| The explicit description of the repugnant (cannibalism, gore, viscera, etc.). Repugnant imagery is straightforward and understandable: it is the pulling back of the curtain on the uglier sides of fantasy; showing the reader things they would rather not see. | |

| “Wrongness” |

|

| “Wrong” imagery takes an image that the reader is intimately familiar with (e.g. the human body) and twists it, placing it at odds with the reader’s accepted norms. Think of the grotesque, hunched physique of Mr. Hyde in Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde |

|

| Cultural Legacy |

|

| Every culture has its ghost stories, folk tales, and frightening myths. Devils, demons, cannibals, etc. lurk somewhere in every zeitgeist. George A. Romero’s living dead are a recent addition. These images can be utilized by creators as a short-hand for all of the other imagery. The very word “zombie” conjures certain images in the reader’s mind, and creators can use that cultural legacy either to “shortcut” some narrative or to “level-set” the reader’s mind-set. Or consider Stephen King’s usage of the clown Pennywise in It. While this is a useful (and often powerful) tool, it should be used judiciously as over-reliance can leave the work feeling trite or comedic in nature. |

So as you lie in wait for monsters to come trick or treating to your door, try to think a little bit about the horror genre. What makes it good? What makes it horrific? Maybe you can add a little more horror into your Halloween? And please, let me know if you can think of any other tools that creators of excellent horror utilize. I’d love to add them to my ghoulish toolkit.

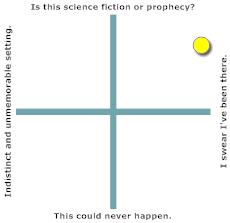

With that being said, and in the spirit of Halloween, allow me to leave you with an image I have always found fun and terrifying. Happy Halloween!