Accessibility: Speculative Fiction’s Pernicious Strawman

NOTE: My thinking here is a bit of a tangential response to some of John H. Stevens’ recent Erudite Ogre columns over at SF Signal. I strongly recommend those columns as an insightful exploration of genre and genre identity. Here’s a link.

Once we create a work of art, the next step is to get that work into the hands of the largest (hopefully appreciative) audience we can. That’s a natural and universal desire, and it is this desire that lies at the root of the ever-present question faced and posed by speculative fiction writers: how can we get more people to read speculative fiction? But a real, substantive answer to that generalized question is a lot more complicated than the question itself. Which is why, more often than not, we re-formulate that question into the more tractable: why don’t more people read speculative fiction?

That question tends to elicit a Pavlovian response among fans and creators alike: SF needs to be more accessible. Characters over idea. Et cetera, et cetera. Unfortunately, the question and its stock answers suffer from three related problems: first, they observe non-existent symptoms (audience disinterest in speculative fiction), and then misdiagnose the causes of their incorrect observations (accessibility), and prescribe the wrong medicine for the wrong illness (making SF more accessible).

Hypochondria in the Speculative Genre

The rumors of speculative fiction’s demise have been greatly exaggerated. Those who claim that interest in speculative fiction is flagging must be living on a different planet. Consider:

- Box Office Results. This past weekend, six of the top ten grossing movies were explicitly science fiction, fantasy, or horror. According to Rotten Tomatoes, their combined weekend gross was over $120 million, which represented 83% of the top ten combined weekend gross. If speculative fiction no longer resonated with audiences, would they flock to see alien invasions, science-based super heroes battling it out over New York, or vampires?

- Adoption of SF Devices across Genres. Genre fans like to grumble that mainstream literary fiction is “stealing” genre devices (the fact that all literature steals from other literature tends to go conveniently unmentioned). But why would mainstream literary novels – neither marketed at genre cons or with genre markers on the cover – adopt the devices of a “failing” genre? It would be rather counterproductive. And the fact is that they aren’t. In fact, they are adopting new (for their genre) narrative devices that resonate with readers.

- Young Adult Speculative Fiction is Going Gangbusters. The younger generation is devouring speculative fiction. But these younger readers don’t distinguish between science fiction, fantasy, and horror and older readers don’t notice what’s happening in YA (see my earlier rant on this score).

If speculative fiction were dying, then none of these three observable phenomena would hold true. What these trends do mean, however, is that a genre that spent most of its life cloistered in its own “genre ghetto” is now interfacing with a broader community – with new readers and new viewers, who are not as versed with genre history, or who are ostensibly not as focused on the issues that our community holds to (the future! big ideas!).

It is not that this new audience rejects speculative fiction: they simply value different aspects of it, and thus prefer certain types and flavors of SF. That’s evolving taste, and it is nothing new. Every genre – speculative fiction included – is at all times subject to the evolution of taste.

The Misdiagnosed Illness: Accessibility

Those who lament the death of speculative fiction look for a quick fix. That’s only natural, and I certainly understand the impulse. But much of the community tends to see both the illness and the solution in one place: accessibility.

Speculative fiction has spent so long in its ghetto that it has developed a natural superiority complex to “other” genres. This psychology has even filtered into our genre’s discourse: ours is the genre of ideas, ours is “high concept”, we build worlds, etc. That all of these statements are true, however, only makes it easier for us to (by implication) look down on works that lack SF elements. And “accessibility” is more of the same.

The concept of “accessibility” is vast, and it does contain many facets. But the least complicated, most easily-grasped dimension is that accessibility equals simplicity. When many of us say that SF needs to be “more accessible” what we are really saying is that it needs to be “less challenging” or “simpler”. You know, so that mainstream folks “can get it”. Fewer neologisms, less science, more unobtanium, etc. This is a solution that lets us retain our superiority: after all, we are the cognoscenti who grok the rarefied heights of speculative fiction. But to be more popular, we have to dumb it down for everyone else.

This type of thinking is wrong-headed. The fact is that “everyone else” groks SF just as much as we do. That’s why consumers lap it up in film, books, comics, television, etc. Time travel, alternate reality, dystopia, space travel, magic…these are no longer outré narrative devices: they have entered our social consciousness, have been absorbed and internalized by popular culture.

Terms like “accessibility” are dangerous because they make it too easy to prescribe simplistic and inaccurate solutions. For too many, they mischaracterize the symptoms, misdiagnose the illness, and prescribe the wrong treatment.

Engage-ability vs Accessibility

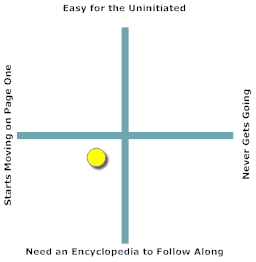

The dimension of accessibility that, I think, makes more sense and is more helpful (and more accurate) is not the degree to which a work of fiction is “accessible” or not. Instead, it is the degree to which its audience can engage with it.

Some might say they are the same, but that’s incorrect. Accessibility is a negative concept: it implies that someone “can’t get in.” But engagability (and yeah, I know that isn’t really a word…but it should be!) is a positive concept, and it is a lot more difficult to both define and achieve. To make a work more accessible is simple: just make it easier to follow, easier to understand. But how to make a work more engaging? How do we make a work of art more compelling for our audience? That is the question that keeps artists up at night, always has and always will.

Engagement with a work of fiction is driven by a host of factors, and the balance between those factors among different readers will vary significantly. That’s why it is so complicated. Some of us might value plausibility over excitement, or characterization over world-building. And even these are false dichotomies: the reality is a spectrum spanning all aspects of narrative.

Alas, I don’t have a prescription. I wish I knew how to make stories more engaging. I have my theories, but they work for me as a reader and me as a creator and might not work for either other readers or other creators.

If we write the stories we care about – stories that engage us intellectually, emotionally (whatever pushes our personal buttons) – then odds are those stories can find a like-minded audience. Getting the word out, informing that audience of these stories’ existence, is an entirely different challenge, and one in which the artist is only one actor among many (publishers, booksellers, librarians, reviewers, and yes, readers, all play a role). If we focus on the quality of the work, on making it as compelling and as engaging as possible, then by doing so we maximize the likelihood that it will develop a devoted audience. And an entirely separate discussion should be had around the marketing and promotional methods that can help maximize that audience’s size.

As creators of speculative fiction, we should rejoice that our potential audience – that segment of the population who can grok the devices we employ – is now so large, and growing every day. We should credit them with the intelligence to recognize compelling art when they see it. After all, we don’t like it when mainstream literary snobs condescend to us. Should we really return the favor?