REVIEW: The Night Sessions by Ken MacLeod

|

Title: | The Night Sessions |

|---|---|---|

| Author: | Ken MacLeod | |

| Pub Date: | April 3rd, 2012 (US reprint) August 7th, 2008 (UK original) |

|

| Chris’ Rating (5 possible): |   |

|

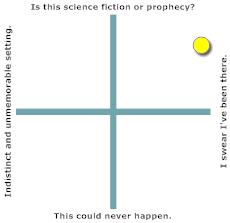

| An Attempt at Categorization | If You Like… / You Might Like… | |

|

||

Science fictional world building is a double-handed balancing act. On the one hand, it teeters between the communication of relevant facts to the reader and the maintenance of the narrative’s forward momentum. On the other hand, it wobbles between the implausibility of the conceit and the effort the reader must make to accept it. When either of these two balancing acts tilts in any direction, it threatens to upend the other. And in Ken MacLeod’s hard SF thriller The Night Sessions, the string that ties them together is the year 2037, when the book is set.

The Night Sessions is a near-future police thriller: it has a crime (the murder of a Roman Catholic priest), and it stars an engaging though forgettable crime solver (DI Adam Ferguson), who uncovers a complicated conspiracy with extremely high stakes. What sets MacLeod’s thriller apart from the usual fare is its near-future science fictional world. The book is set in 2037, in a society that has managed to erect a pair of space elevators, developed ubiquitous self-aware robotics, and whose recent religious wars have led to the global primacy of political and cultural secularism/atheism.

It is an ambitious work that tries to marry the thriller’s frenetic pace with classic hard SF themes of robotic faith. And in this case, I found the marriage a bit rocky. Structurally, police thrillers count on their high-stakes action and non-stop pacing to keep the reader flipping pages. We get so wrapped up in the events of the story that we don’t have time to consider its plausibility, or to really examine the hero’s leaps in logic. Thrillers rely on the speed of the narrative train to keep us from counting its rivets. But in the case of The Night Sessions, MacLeod’s pacing gets swamped by world-building.

The book features a fascinating vision of a future Edinburgh (and to a lesser extent, a future New Zealand). The settings, and the characters’ interactions with them, make for a great extrapolation of contemporary technology trends (MacLeod’s conjectures about augmented reality and self-aware AI are particularly well-rendered). The sociological concept of people willingly abandoning religion, of faith becoming an embarrassing family secret, is the type of high-concept theme that brings to mind classics like Walter Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, James Blish’s A Case of Conscience

, Robert J. Sawyer’s Calculating God

, or Anthony Boucher’s “The Quest for St Aquin”. It was the idea of exploring how such a society came about and what life in such a society might be like which first drew me to the book. Yet because the story is set in 2037 (which isn’t that far off), MacLeod bent over backwards to establish how our world gets from where we are today to where his fictional environment becomes possible, and in doing so slowed the book’s pace significantly.

World-building is a particular challenge for near-future SF. When we write a story set one, two, or even twenty years from now, we always run the risk that life will outpace fiction. Far-future SF, or SF that is utterly removed from our contemporary environment, ducks this problem by asking us to accept the fictional environment as-is. Larry Niven’s Ringworld, Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels

, Alistair Reynolds’ Revelation Space stories

, or Frank Herbert’s original Dune

are great examples of this at work: the scientific, sociological, and cultural conceits that are needed to make the story possible are easily accepted because the setting is fundamentally divorced from our reality. In one sense, they are secondary world fantasies, however plausible the science in their construction. Yet when a story is set in the near-future and on our planet no less, it automatically asks the reader to consider how our world gets to become the fictional one.

It is a challenge that some authors, notably Ian McDonald (especially in The Dervish House, see my earlier review), Paulo Bacigalupi, William Gibson, or Cory Doctorow (particularly in Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom

) do very well. The trick, it seems to me, rests in avoiding history lessons. For example, in The Windup Girl

, Bacigalupi wastes very little time on a high-level, abstract discussion of the ecological disaster that makes his fictional world possible. Instead, we see the near-future environment that his ecological disaster wrought filtered through the prism of his characters’ experiences. His characters know their world, live in their world, and we learn its dimensions and history through their perceptions of it. This technique is one which the New Wave’s sociological SF popularized in the ’70s, and which was further honed by the cyberpunk movement in the ’80s and ’90s. When done well, it takes a book’s themes and artfully expresses them through the story’s unfolding action, wasting no time (read: word count) on explanation when implication will suffice.

MacLeod, unfortunately, chose a different route. He painstakingly explains to us the history of his world’s Faith Wars (which he tells us began on September 11, 2011, and which were economically tied up with oil), and how they led to a (apparently global) rejection of religion, how global society grew disgusted the atrocities of war, and by society’s subsequent rejection of the faiths that spawned it. The book’s first half is essentially devoted to explaining this history and to establishing the characters’ relationships to it. This is a significant departure from a thriller or police procedural structure, and it is one which does the story no favors. Because so much of the book’s first half was explanatory, I found myself spending too much time questioning its conceits.

Even if I accept global disillusionment with faith, thirty years is an awfully short period of time for people to forget basic components of major global religions. MacLeod expects us to believe that his hero, who was raised in a society where religion was present, who served on the police force’s “God Squads” in persecuting religious citizens, has forgotten basic terminology associated with Christianity. I have difficulty believing that cultural concepts like the privacy of the confessional would be forgotten so quickly.

Furthermore, the book focuses exclusively on the Judeo-Christian faiths, with some off-hand references to Islam. This is somewhat understandable considering that the book is primarily set in Edinborough, with its strong Presbyterian and Calvinist traditions. But with MacLeod’s painstaking explanation of his world’s history, the lack of reference to Hinduism, Buddhism, or any of the other non-Catholic/Protestant denominations of Christianity (Greek or Russian Orthodox, for example) was striking. I suppose that it is possible that I missed a glancing reference somewhere, but as far as I noticed, there was precious little discussion of any religion outside of the Christian worldview. Where were the world’s other major religions during the Faith Wars? Where are they in MacLeod’s 2037?

Second, thirty years is an incredibly short period of time for a war-ravaged society to develop self-aware artificial intelligences and deploy them ubiquitously throughout society. The technological concept is interesting, the way that the robots operate within MacLeod’s fictional society is insightful, and the thematic exploration of AI and faith is reasonably well-executed. But frankly, I thought it unlikely that in twenty-five short years we might be at that point…especially if – as MacLeod makes clear – the United States was ravaged by a second civil war after the Faith Wars. I might be willing to offer a pass on the advanced technology: the Faith Wars would likely have spawned a lot of frenetic technological development, and MacLeod makes clear that the AIs were initially military technology. But for such technology to get broad distribution throughout society (rich and poor alike) in so short a time period also struck me as somewhat implausible.

However, these issues really only affected the book’s first half. By the second half, the world-building is mostly out of the way and allows us to buckle up for an exciting thriller. Though there is a bit of deus ex machina in places, and the unmarked perspective shifts were a bit jarring, the second half is paced well enough to be fun and intellectually engaging. While the doubts I experienced about MacLeod’s world-building continued to flutter in the back of my mind, I was able to get past them to enjoy the overall story.

The themes of faith, ecology, economics, justice, and identity that MacLeod explores were all interesting, but I felt that they all got fairly short shrift. With so many interesting concepts raising so many compelling questions, the relatively short novel was spread too thin to adequately explore all of them. Thankfully, novel’s the central question of machine faith gets just enough attention to ultimately be satisfying.

To be clear, despite its weaknesses Night Sessions is an enjoyable book, and it is ambitious. But it is not without its problems. It would have benefited greatly, I felt, from more rigorous attention to the methods of world-building, and to their relationship with the book’s pacing.

Fans of hard science fiction who are looking for an intellectual, mind-game playing book will likely enjoy Night Sessions, though they may find some of its conjecture irregular and implausible. Readers looking for a science fictional thriller will likely be disappointed by the book’s slow-paced first half, but may find that the conclusion makes up for the first half’s weakness. But readers who enjoy near future SF, and in particular those who are willing to deal with the challenges endemic to that sub-genre in exchange for stimulating extrapolation of current technological/economic trends, will find a lot to enjoy in Night Sessions

.