My apologies for posting this on Wednesday, rather than Tuesday. I know I’m late, but I got caught up with day-job work and so…sorry. Hope the timely review makes up for the delay.

The word “epic” gets thrown around more often when talking about fantasy than a well-aimed dagger. I’ve seen it applied (and done so myself) to Tolkien, Brooks, and Donaldson, to Jordan, Martin, and Eddings, to Jemisin, Rothfuss, and Sanderson, and the list goes on. In most of these cases, the word “epic” is an apt descriptor. But I would argue that Steven Erikson and his ten volume Malazan Book of the Fallen out-epic all of these other epics in its epic-ness. The world created by Steven Erikson and Ian C. Esselmont, each individual book in Erikson’s series, and the complexity of the story Erikson planned out from the beginning: each of these alone can be justly described as epic in scope, epic in scale. But in this genre that tosses around the E-word like it was going out of style, I believe that Erikson’s ambition is the most epic of all. And having now read Erikson’s The Crippled God , the tenth and final installment in his Malazan Book of the Fallen, I believe that Erikson delivered on the “epic” promised back in 1999.

, the tenth and final installment in his Malazan Book of the Fallen, I believe that Erikson delivered on the “epic” promised back in 1999.

DISCLAIMER: I am not saying that the Malazan Book of the Fallen is “better” than the Wheel of Time, or A Song of Ice and Fire, or the Belgariad, or Shannara, or insert-your-favorite-fantasy-series-here. However, I do believe that it is different. This difference especially applies to its world building and plot structure, and in many respects to its themes and characterization. In its plot structure and world building especially, I find it far more complex than those other series I just mentioned. But “more complex” does not mean better. It just means more complicated.

A little over eleven years ago I was waiting to board a transatlantic flight in Warsaw, Poland, idly browsing the tiny English-language section of a little airport bookstore, when I stumbled across a thick book. Tantalizingly titled Gardens of the Moon , by an author I’d never heard of before, and with a cover not-quite-sf/not-quite-fantasy by Chris Moore that instantly set it apart from the contemporary Chihuahua killer epic fantasies of Jordan, Martin, and Goodkind, I had to buy it. I spent the next nine or ten hours sucked into Steven Erikson’s visceral, violent, gripping world. Since that fateful afternoon, I have eagerly anticipated each new volume in Erikson’s opus, and so it was with childish delight (and squeeing) that I stumbled upon a copy of The Crippled God

, by an author I’d never heard of before, and with a cover not-quite-sf/not-quite-fantasy by Chris Moore that instantly set it apart from the contemporary Chihuahua killer epic fantasies of Jordan, Martin, and Goodkind, I had to buy it. I spent the next nine or ten hours sucked into Steven Erikson’s visceral, violent, gripping world. Since that fateful afternoon, I have eagerly anticipated each new volume in Erikson’s opus, and so it was with childish delight (and squeeing) that I stumbled upon a copy of The Crippled God two days before its official pub date in my local Borders.

two days before its official pub date in my local Borders.

Gardens of the Moon by Chris Moore (via Wikipedia)

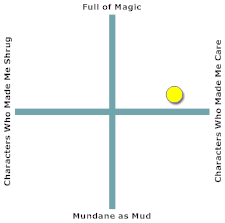

To read Erikson’s work, one must be prepared to immediately suspend disbelief, and to dive headfirst into a world rich with layers of history, culture, politics, and mythology that would make Tolkien’s head spin. Readers not already well-versed in the conventions of the fantasy genre might find it all a bit confusing at first. But for those readers able to suspend their disbelief, and who are prepared to intuit or await elucidation, the Malazan Book of the Fallen is an immensely enjoyable series. The Malazan world was created by Steven Erikson and Ian C. Esselmont in their role-playing campaigns. But the two brought to their creation their extensive expertise in anthropology and archaeology, resulting in a world with intricate, distinct cultures, complex historical societal relationships, economic balances, and military history.

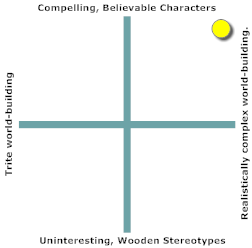

Over the course of the ten book series, we follow many (I lost count at around forty five) distinct groups of characters. Some groups are small, numbering maybe one or two members, while others are large factions with many characters going nameless. However, each of these groups is presented completely, meaning that they are drawn as round (using E.M. Forster’s definition), fully-fleshed characters. Erikson shows us everyone’s fears, doubts, concerns to such a degree that by the time we’re halfway through the first book, the very concept of “hero” and “villain” has lost all meaning. It is this moral ambiguity, this rationalization and justification of character choices and ethical mistakes, that drive the series’ themes.

The first five or six books in the series are self-contained wholes. The events of each book occur non-linearly, following several distinct “tracks” of events separated by both time and space. The main tracks comprise different books in the series, at least in the beginning. This makes it possible for a reader to start either with Gardens of the Moon (Book 1), or say Deadhouse Gates

(Book 1), or say Deadhouse Gates (Book 2), or Memories of Ice

(Book 2), or Memories of Ice (Book 3).

(Book 3).

Reading them in order of their publication, I was initially surprised and confused by their non-linearity. Where were the characters I had met and fallen in love with in the earlier books? What had happened to them? What were they doing? But like a master weaver, Erikson successfully introduces new strands while maintaining interest in those that came before. This separation across books in the series begins to collapse around Midnight Tides (Book 5), where a new reader coming into the story would be so completely lost in the whirling politics of gods, cities, armies, factions, squads, races, creeds, etc. as to make it an exercise in futility.

(Book 5), where a new reader coming into the story would be so completely lost in the whirling politics of gods, cities, armies, factions, squads, races, creeds, etc. as to make it an exercise in futility.

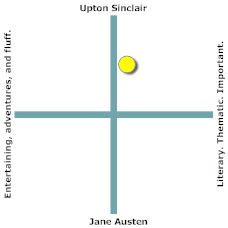

It is at this point in the series (books 6 – 8), that Erikson stumbles for the first time. This stumble is interesting to note, precisely because it touches upon his introduction of higher-level, more abstract philosophical themes into the story. The first six (arguably seven) books are largely plot driven. We follow the striving of different groups of characters – especially the Malazan military – as they attempt to achieve their goals. The books are thematically interesting, but there is a palpable sense that reader doesn’t yet know everything. In the sixth, seventh, and eighth books, Erikson thickens the plot by explaining more complex historical relationships, and introducing new gods, and new players. The introduction of this history, and metaphysical motivation for certain characters introduced in the eighth book, slows the pacing significantly. These latter books remain readable, but I had to read them at least twice in order to really understand what was happening. They are not bad, but they are much more dense than the other books in the series, and those books are already more dense than most epic fantasy fare. Thankfully, Erikson again hits his stride in Dust of Dreams (book nine) as he now has all of the actors on stage and moving towards the climax in The Crippled God

(book nine) as he now has all of the actors on stage and moving towards the climax in The Crippled God .

.

And what a climax! The series tracks several hundred (again, I lost count) distinct plot lines. But they are all brought together in the tenth and final book. Perhaps more importantly, it is also in the The Crippled God that we see the thematic lines from the earlier books brought together. The thematic convergence in The Crippled God

that we see the thematic lines from the earlier books brought together. The thematic convergence in The Crippled God is one of the most impressive aspects of the series. Each of the earlier books has its own themes, which are in and of themselves complicated and well-executed. But after reading The Crippled God

is one of the most impressive aspects of the series. Each of the earlier books has its own themes, which are in and of themselves complicated and well-executed. But after reading The Crippled God , the themes of earlier books are either clarified, corrected, or shown as illusory. Unifying these disparate (and oftentimes contradictory) themes without invalidating them is a neat trick, and makes the intellectual and emotional exercise of the whole series quite worth it.

, the themes of earlier books are either clarified, corrected, or shown as illusory. Unifying these disparate (and oftentimes contradictory) themes without invalidating them is a neat trick, and makes the intellectual and emotional exercise of the whole series quite worth it.

From a stylistic standpoint, Erikson takes more from the gritty, boots-in-the-mud fantasy of Glen Cook than he does from the elf-and-dwarf high fantasy of J.R.R. Tolkien. Erikson’s primary characters are soldiers, and he draws them as imperfect, swearing, and swaggering. While dragons, and Erikson’s version of elves feature quite prominently, his characters are very far removed from Smaug or Legolas. It is the darkness and grit of his world that makes it compelling, that subverts the traditional tropes of the genre. Dragons as mad almost-gods? Heroes who (along with the reader) are ignorant of their quest, and just have to do as they’re ordered? These are fun subversions.

I found Erikson’s take on women in his books particularly interesting. Historically, I have often found fantasy to be full of stereotypical square-jawed male hero-types, with damsel-in-distress ladies swooning in the wings (if they are present at all). Erikson’s female characters are more likely to break a hero’s jaw than pine or swoon. They are soldiers, and conspirators, and commanders equal in all respects to the men, while still evidencing deft characterization that makes them fully believable. Both the men and women are flawed, emotional, sometimes angry, sometimes not. Erikson makes them complex, while retaining their intrinsic humanity. Which is refreshing in a genre often dominated by particular molds.

I have spent the past twelve years with these characters. Their stories have in many respects become a part of me, like old friends. The tenth book brings Erikson’s enormous cast of characters together, and wraps up their stories. With one or two (notable) exceptions, we learn what happens to everybody, how they end up. The tenth book is in many respects about closure, and Erikson unflinchingly brings the story of different groups and characters to a close. But – and this is one of his points – even though the book gets closed for some characters, life goes on. The unity of character, plot, theme, and execution in this tenth book is singularly impressive.

However, for everything good about his work, the complexity – of his characters, plots, themes – can be quite off-putting. One reader (whose opinions I respect greatly) very much dislikes Erikson’s work. She claims that it is too hard to follow, impossible to keep the myriad characters and plot lines straight even within a single book, let alone across a ten book series. For many readers, this will be a valid criticism. Erikson has produced a truly dense, complicated work of fiction. Myriad plot lines, more characters, complicated races that often go by different names, complex battle scenes shown from the perspective of multiple soldiers in the thick of it, this is writing that demands real work from the reader to keep things straight, to follow along with events. I found myself often having to read or re-read sections (and in some cases, entire books) just to really figure out what the heck actually happened. For many, this will be a weakness: why should I have to work so hard for my fiction? But I personally found that I enjoyed doing that work, that I enjoyed getting to spend time in an ugly, dark fantasy world that was realistically built while still employing the tropes of fantasy.

Back in 1999, Erikson told fans that the Malazan Book of the Fallen would be a nine book series. Like any gargantuan epic, this was an ambitious goal. However, Erikson executed on this ambition both in the creative sense, as well in the practical sense: publishers and fans like to see epic series come out with new installments on an annual basis. Publishers like it because it helps them push paperback editions of the earlier books, and fans like it because we can still remember what’s going on in the story. But in a sub-genre famous for delays (George R.R. Martin’s A Dance of Dragons has been delayed five years already and still counting), it is incredibly refreshing to come across an author whose ambition is so vast, whose story is so complicated, but who still manages to produce quality work reasonably on schedule. It’s refreshing, and my hat is off to Erikson for delivering on his vision.

Although I have read that Erikson is planning a new eleven book arc in the Malazan world, The Crippled God represents in many ways the end of an era. It is a masterfully-executed conclusion to a complicated, ambitious, dense opus. On the one hand, I am glad that the series is over, that Borders screwed up and I managed to get my hands on a copy several days before its official release, and that Erikson satisfied my (high) expectations from it. But on the other hand, I will miss the anticipation of the next book, will miss getting to laugh and cry with the characters I’ve enjoyed over the last twelve years.

represents in many ways the end of an era. It is a masterfully-executed conclusion to a complicated, ambitious, dense opus. On the one hand, I am glad that the series is over, that Borders screwed up and I managed to get my hands on a copy several days before its official release, and that Erikson satisfied my (high) expectations from it. But on the other hand, I will miss the anticipation of the next book, will miss getting to laugh and cry with the characters I’ve enjoyed over the last twelve years.

Erikson’s Malazan Book of the Fallen is a complex, involving, and emotionally powerful epic fantasy series. There is no series more deserving of the word “epic”. Pick up a copy of Gardens of the Moon , and see if you like it. Be prepared to work at it, because it is difficult. But difficult does not mean bad, and rest assured that by the time you get to The Crippled God

, and see if you like it. Be prepared to work at it, because it is difficult. But difficult does not mean bad, and rest assured that by the time you get to The Crippled God , you will find your investment has been fully justified and amply rewarded.

, you will find your investment has been fully justified and amply rewarded.

Malazan Book of the Fallen by Steven Erikson

is a solid, enjoyable book that continues to showcase Martinez’ facility with genre tropes.

follows Diana, a vaguely-down-on-her-luck coat salesperson, who manages to land a great apartment. However, that apartment opens up Diana’s mind to all of the dark, Lovecraftian monsters that have stumbled into our reality. Diana must deal with the creatures in her apartment, the twisted realities of her entire apartment building, and ancient gods who want to devour the moon. All in a day’s work, right?

– like Martinez’ earlier books – lacks the gonzo anything can-and-probably-will happen world-building of Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

. And while it shares Pratchett’s serious-story-grounded-in-a-comedic-setting framework, Martinez’ world is more firmly grounded in our reality than Discworld, where everything becomes grist for Pratchett’s parody mill. I would argue that Chasing the Moon

is not a parody at all, but that Martinez uses humor to show what makes us human.

, there were two aspects that left me vaguely unsatisfied. It’ll be a little difficult to explain without giving any spoilers, but here goes nothing:

is clear. But while Martinez manages tension very adroitly, that tension never veers into the gut-wrenching, abyssal horror that was emblematic of the classic Weird Tales pulps. Perhaps I’m a little jaded, or perhaps Martinez’ heroine is a little too plucky, a little too ready to deal with the horrors she faces. The tension escalates nicely, but I found myself reading it more like an adventure story than a cosmic horror tale. That being said, it reads as a very strong adventure story.

. It is a fast-paced, really engaging read. Much like life, it has its moments of laugh-out-loud humor, coupled with moments of deep emotion. If you enjoy Tom Holt

, John Scalzi’s Agent to the Stars

, or Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett’s Good Omens

, I expect you will get a particular kick out of it. It’s a great summer book, perfect for reading on the beach…although beware of tentacles reaching up from the depths.