REVIEW: Mockingbird by Walter Tevis

|

Title: | Mockingbird |

|---|---|---|

| Author: | Walter Tevis | |

| Pub Date: | 1980 (original) June 2007 (reprint) |

|

| Chris’ Rating (5 possible): |      |

|

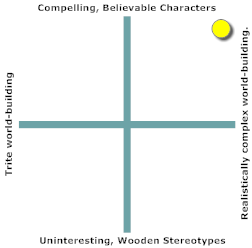

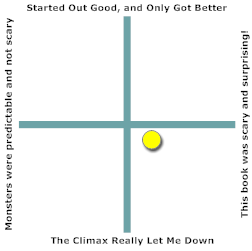

| An Attempt at Categorization | If You Like… / You Might Like… | |

|

||

With Tor.com celebrating “dystopia week” not too long ago, I decided to read Mockingbird by Walter Tevis. Reprinted about four years ago in Gollancz’s fantastic SF Masterworks line, it had been sitting on one of my “to read” shelves for quite a while before I threw it into my travel bag for a business trip. I wasn’t reading it with an intent to review it: all I knew about the book was that it was supposed to be a classic dystopia that I’d never read. But the book had such an impact on me that I felt like I just had to share some of it with you.

The book opens with Bob Spofforth, a “Make Nine” android, enacting a private annual ritual: he tries to throw himself off of the top of the Empire State Building. But his programming prevents him from doing so. The narrative description in the the first chapter paints an utterly believable image of 25th century Manhattan: buildings still stand, buses still run (sort of). The city remains recognizably New York, but humanity has faded and turned inward. Skyscrapers line the streets like Mastodon bones bleached in the sun, and it is through the clinical, analytical description seen over the shoulder of Bob Spofforth that we get the sense of mankind receded, silent, and sad.

Through Spofforth, we learn that some time ago humanity came to believe in a principle of supreme privacy: that so much as talking to another person or looking them in the eye can impinge upon that privacy. Like soma in Huxley’s Brave New World, Tevis’ humans rely on drugs to help manage their moods and adjust their daily lifecycle. With machines to do everything for them, with indoctrinated cultural rules about privacy in force, humanity is rudderless, with no purpose, direction, or even concept of such. The robots are there to do it all for them. And since no humans remain who can repair the robots, the machinery that keeps society treading water is slowly breaking down.

Spofforth is a suicidal tyrant more human than many of the actual people we meet in the book. He knows that the species homo sapiens is dying out, with negative population growth. Into Spofforth’s Manhattan comes Paul Bentley. At first blush, the reader expects Paul to be a Promethean figure, having discovered a version of the Rosetta Stone (a film through which he could match words to a reading primer) and taught himself to read. Paul offers to teach others how to read, but instead Spofforth assigns him to do audio-recordings of the title cards in ancient silent films.

Paul is fundamentally a flawed hero. Despite his one act of initiative, he remains a product of his society: unwilling and unable to transcend the limits imposed by his value system. He does as instructed, despite niggling hints of rebellion in the back of his mind. Then, he meets Mary Lou: a dyed-in-the-wool rebel living in the city zoo who refuses to live by society’s neat rules. He introduces her to reading, and together the two of them re-discover the written word. It is this section of the book – perhaps the book’s first half – that reduced me to tears. Watching Paul and Mary Lou learn to read taps into everything wonderful about books, language, love, beauty, and what makes us human. Using the simple, limited vocabulary of a functional illiterate Tevis subtly broadens his characters’ horizons with masterful subtlety. Tevis suggests that our desire and ability to read are at the core of what makes us human, and that the moment we lose touch with the written word we risk fading into meaningless despondency.

The second half of the book remains solid, but I didn’t find it as emotionally powerful as the first. Shortly after Spofforth discovers Paul and Mary Lou’s exploration of reading, he has Paul arrested and sent to prison. In prison, Paul must develop the independence of spirit to break free and return to New York and Mary Lou. It would not be fair to say that the second half of the book is weak: it is not, and the final climax that resolves the fates of our three heroes (Paul, Mary Lou, and Spofforth) is particularly poignant. But despite the quality of the second half, it is the first which remains heart-wrenchingly perfect.

As I mentioned last week, I disagree with Jo Walton’s argument that dystopia isn’t science fiction. But Tevis’ Mockingbird does offer her POV some evidence. Looking at his career in total, it’s a bit of a stretch to call Walter Tevis a science fiction writer. Of his six novels, only two (Mockingbird

and The Man Who Fell to Earth

) can be called science fictional. The others (of which The Hustler

and The Color of Money

are probably the best known) are all mainstream literary works, several of which have been adapted into excellent movies.

However, Mockingbird does employ some of the techniques earlier put to work in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four or Huxley’s Brave New World

. Where Tevis departs from the earlier dystopian mode is to present his dystopia not as the consequence of people-who-know-better controlling the sheep. There is no “grand conspiracy” at work to keep mankind down. In fact, the only character who has the power to enforce such a conspiracy (Bob Spofforth) is as much a prisoner of the dystopia as our human heroes. This adds a dimension to Mockingbird which I find particularly interesting, as it places the blame on creating a dystopian world squarely on its creators: us.

Gollancz has consistently excelled with their SF Masterworks and Fantasy Masterworks series, and the actual physical product of Mockingbird is very well done. It sports an attractive cover by Dominic Harman which really sets the tone for the grim, dark world of 25th century Manhattan. And – much like Tevis’ book – it suggests that hope may be just around the corner.

On the whole, Mockingbird is hands-down the best dystopia I have read in a very long time. It provides an emotional and philosophical gut-punch that is difficult to rival. I think this is a must-read book for anyone who loves books, who loves reading, and who loves language. In the passages where Paul discovers new words and ways of looking at his life we can find all the truths of the world.