REVIEW: The Half-Made World by Felix Gilman

|

Title: | The Half-Made World |

|---|---|---|

| Author: | Felix Gilman | |

| Pub Date: | October 12, 2010 | |

| Chris’ Rating (5 possible): |     |

|

| An Attempt at Categorization | If You Like… / You Might Like… | |

|

||

The Half-Made World by Felix Gilman is the gripping story of war on a brutal frontier. This is Gilman’s third book, after his excellent 2007 debut Thunderer

and its disappointing sequel Gears of the City

. Set in an entirely different universe, The Half-Made World shows that Gilman has clearly disciplined his imagination and gained a focus that had been lacking in his last novel.

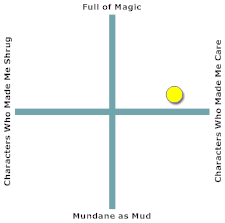

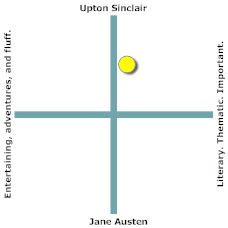

If you are looking for steampunk with Victorian mannerisms and airships, look elsewhere. While it shares elements of the steampunk aesthetic, it is firmly rooted in the oily, Wild West and Sinclair’s blood-stained Chicago stockyards. For those critics who complain that steampunk never has anything important to say, I recommend they read this book. It takes place in (as the title would suggest) a half-made world, where the east is settled and established, operating along “realistic” lines. The west remains wild, and reminds me of the aboriginal Dreaming. The rules that govern it are shifting, changing, and magic (of a sort) is real. From a thematic standpoint, The Half-Made World is a serious examination of the complex and conflicting values inherent in the romantic and manifest destiny movements of the 19th century. But despite its important themes and artful writing, it is an entertaining and exciting read, striking that rare balance between adventure and literature.

Gilman’s frontier is torn apart by an unending war between the Line (railroads, trains, manifest destiny) and the Gun (guns, fatalistically doomed heroes, romance). When the book opens, it is entirely plausible that the Line and the Gun are merely the colloquial names for a set of combating ethos: symbols, and little besides. But it quickly becomes apparent that these opposing forces are in fact very real spirits or demons, who embody particular mores and values and who attract particular types of followers. The opposing cultures of Line and Gun, and the setting they create, are some of the most important characters in this book.

The story is told from three perspectives:

- Lowry, an agent of the Line,

- John Creedmor an agent of the Gun, and;

- Liv Alverhuysen, a “neutral party” from the settled East swept up in the frontier conflict.

While each of the perspective characters is engaging, the Line and the Gun themselves provide the text with a foundation. Gilman’s writing is extremely tight, and the natures of the Line and the Gun come through in the little details: the methods their agents employ, the territories they control, the people who live under their rule. Even the slight shifts in narrative voice used for the different perspectives help cement the setting. The Line and the Gun are not ephemeral constructs, or religious ideologies. They are real: dirty, smelly, and intensely human forces for all of their inhuman power.

Gilman does something very difficult with his three perspective characters. Each personifies a particular ethos: Lowry is the embodiment of the Line, with all its systematic and methodical values. Creedmor embodies the Gun, with its heroic strengths and tragic weaknesses. Liv personifies a third set of values (still nascent, I would say), which seems designed to balance the Line and the Gun. To paint characters who personify abstract values well is very difficult. It is so easy for them to become caricatures of their mores. Hugo pulls it off exceptionally in Les Miserables. Ayn Rand does it well, though less-reliably than Hugo. While Gilman is not quite as powerful as Hugo, nor (thankfully) as insistent as Rand, his characters remain true to the forces they personify, as well as to their own humanity. They are flawed and identifiable, in a most beautifully human way.

The jacket, designed by Jamie Stafford-Hill and with art by Ross MacDonald, drew my eye in the bookstore, reminding me of the futuristic designs drawn by Albert Robida in the late 19th century. While I don’t think the image depicted on the cover appears at any point in the action of the book, the design is elegant and understated. It captures the spirit of the text, if not its literal action. The book opens slowly, but gathers steam after the first eighty or so pages. The prose is dense, and rich throughout, and Gilman fleshes out his principal and supporting characters gradually over the course of the book. The last third is especially well-paced, and I found myself on the edge of my seat. The perspective and writing remain crisp, and at no point does it come off the rails (no pun intended).

While on the whole this book was excellent, I was mildly disappointed in how Gilman dealt with one of the characters at its end. It is difficult to explain the details without giving anything away, but this is clearly the first book in a larger whole, and to make it self-contained, certain strands needed to be tied up. I understand that, and I understand that there were equally-good or equally-bad options for how to do so. Gilman chose one of them, and his choice is not in and of itself bad and I suspect other readers might be satisfied with it. But when I read it, I found elements of its ending to be slightly anticlimactic, almost bathetic. However, it is entirely possible that bathos was part of Gilman’s point, and while it was disappointing, I find myself waffling on whether it is a weakness or not.

The book ends poised for a continuation of the adventure, without crossing the liminal boundary into cliff-hanger. As a result, I am eagerly looking forward to the sequel. I strongly recommend The Half-Made World to anyone looking for thoughtful steampunk, or who enjoys the frontier adventures of Emma Bull (Territory) or Jeffrey Ford (The Physiognomy

). If (like me) you were turned off by Gilman’s earlier Gears of the City, I’d suggest you give him another shot: The Half-Made World is incomparably stronger in every way.