REVIEW: Stonewielder by Ian C. Esslemont

|

Title: | Stonewielder: A Novel of the Malazan Empire |

|---|---|---|

| Author: | Ian C. Esslemont | |

| Pub Date: | May 10th, 2011 | |

| Chris’ Rating (5 possible): |     |

|

| An Attempt at Categorization | If You Like… / You Might Like… | |

|

||

I’ve mentioned my appreciation of Steven Erikson and Ian C. Esslemont’s gritty Malazan world before, and over the past several years I have eagerly been following Esslemont’s contributions. With Stonewielder, Esslemont’s third book in the Malazan universe, he artfully balances characterization, forward momentum, and complex plotting mechanics to deliver an accessible and enjoyable read.

From his debut with Night of Knives, Esslemont has faced a difficult challenge. By the time his first book was published in mass-market form (2007), Erikson had already released his seventh (Reaper’s Gale

). This meant that Esslemont had a ready audience who would likely snap up his book, but that audience (myself included) had certain expectations.

The first fact that must be stated when describing Esslemont’s work is perhaps the most obvious: Esslemont is not Steven Erikson. The writing styles are different, the plot structures are different, and perhaps most significantly, the pacing is different. However, these differences are not a weakness: in many ways, they make Esslemont’s work more accessible than Erikson’s dense opus. In Night of Knives, Esslemont visibly struggled to get his sea legs. While it was competently executed, there was a tentativeness to his storytelling that had been noticeably absent from Erikson’s work. However, with his second novel – Return of the Crimson Guard

, which takes place after the events of Erikson’s The Bonehunters

– Esslemont clearly grows more comfortable with his plot structures and the intricate flow of multiple storylines. By the time we read Stonewielder

, Esslemont has clearly hit his stride.

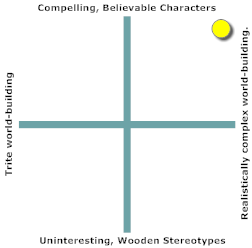

Esslemont’s books tell the story of events on the continent of Quon Tali, literally on the other side of the world from the events of Erikson’s ten book series. Despite the distances involved, the authors share a significant number of characters. Esslemont’s books focus on characters who notably left or vanished from Erikson’s books. This was my first area of concern: how often have we seen new hands mess up a beloved franchise by screwing up the characters? Thankfully, Esslemont neatly avoids this trap, perhaps helped by the fact that his books delve deeply into characters who received less focus in Erikson’s books. As a result, he creates characters that become firmly his own, shaped by and for his own plots and writing style.

The integration between Erikson and Esslemont’s plots – particularly Return of the Crimson Guard and Stonewielder

is excellent. The events of Esslemont’s books have significant repercussions on Erikson’s, and vice versa. However, Esslemont shows us events which Erikson did not, or a different side of those historic events. Reading both Erikson and Esslemont lets us see their world’s history unfold from multiple perspectives. I like to think of it as reading two books on WWII history: one Russian, and one British. They will describe related events, but the different perspectives, cultural backgrounds, styles, and focus will fundamentally change how the same events are presented. Reading one side of the story can be enjoyable, but reading both provides a richer understanding of the events.

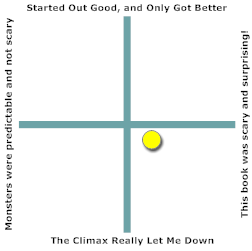

I suspect that read on a standalone basis, the Esslemont books may be easier to follow than Erikson’s. Like Erikson, Esslemont relies on chapter-based POV shifts, but with fewer characters and fewer plot lines it is easier to keep track of what is going on in the story. Stonewielder in particular unfolds in a more linear fashion than Erikson’s typical modus operandi. This focus also helps Esslemont’s pacing, giving the books a certain sense of implacability that draws the reader in. As the stakes rise in Stonewielder

, the pacing likewise accelerates which makes the latter half of the book move very quickly.

Avoiding complex metaphysics helps Esslemont accomplish this feat. While he employs – and elucidates – much of the complex magic of the Malazan universe, he steers clear of the more esoteric metaphysical considerations that bogged down some of Erikson’s later books. The focus on characters in action (or avoiding action, at times) keeps Stonewielder close to its gritty, epic adventure roots.

However, readers unfamiliar with Erikson’s books may find it hard to get become grounded in Esslemont’s novels. My preexisting familiarity with the world’s bewildering factions, history, politics, and characters let me hit the ground running with Night of Knives, and smoothly follow Return of the Crimson Guard

and Stonewielder

. How daunting a fresh reader would find these titles and the unique world they present is difficult for me to judge.

On the whole, Ian C. Esslemont’s Stonewielder is a great addition to the Malazan canon. The plotting, characterization, and pacing are strong, and he continues to apply the excellent world-building characteristic of the Malazan universe. At its heart, Esslemont’s story strikes me as less complicated than Erikson’s. As such, I found it a welcome breath of fresh air coming off of the satisfyingly dense conclusion to Erikson’s series. Those who started reading Esslemont with Night of Knives

will be pleased to see that his craft has significantly improved over the last several years.

If you’re a fan of gritty, complex, ambitious epic fantasy then Stonewielder will likely appeal to you. It combines the gritty boots-in-the-mud feel of Glen Cook’s Chronicles of the Black Company

, with morally ambiguous eldritch magic like in Michael Moorcock’s Elric Saga

, and the evocative world-building of Steven Erikson’s Malazan Book of the Fallen

series (which shouldn’t be surprising, considering that Ian C. Esslemont co-created the Malazan world with Erikson).

To flatten the steep learning curve and get some of the characters’ backstory, I strongly recommend starting with Return of the Crimson Guard, or Steven Erikson’s Malazan Book of the Fallen series. If anyone reading this has instead started with the Esslemont books, I’d be curious to know how you found them. Were you able to get drawn into the world, fill in the blanks of backstory and factions, and generally follow along?

In the meantime, I’m going to be eagerly awaiting the next installment in Esslemont’s series. If his work continues to improve as it has so far, then his series might gain in heft to become more than a side story in the Malazan universe. The seeds are certainly there, and I’m rooting for the series’ continued upward trajectory.